History of the Roman Catholic Church

- History of the Roman Catholic Church

- 1 Background and Definitions

- 2 Church Historical Events

- 3 Formulation of Bible

- 4 Doctrinal Development

- 5 Persecution

- 6

Councils and Heresies

- 6.1 List of Ecumenical Councils

- 6.1.1 Council of Jerusalem

- 6.1.2 First Ecumenical Council: Nicea I (Arianism,Gnosticism) (325)

- 6.1.3 Second Ecumenical Council: Constantinople I (Macedonianism, Pneumatotomachianism) (381)

- 6.1.4 Third Ecumenical Council: Ephesus (Nestorianism) (431)

- 6.1.5 Fourth Ecumenical Council: Chalcedon (Monphysitism) (451)

- 6.1.6 Fifth Ecumenical Council: Constantinople II (553)

- 6.1.7 Sixth Ecumenical Council: Constantinople III (Monothelitism) (680-681)

- 6.1.8 Seventh Ecumenical Council: Nicea II (Iconoclasm) (787)

- 6.1.9 Eighth Ecumenical Council: Constantinople IV (869)

- 6.1.10 Ninth Ecumenical Council: Lateran I (1123)

- 6.1.11 Tenth Ecumenical Council: Lateran II (1139)

- 6.1.12 Eleventh Ecumenical Council: Lateran III (1179)

- 6.1.13 Twelfth Ecumenical Council: Lateran IV (Albigensianism) (1215)

- 6.1.14 Thirteenth Ecumenical Council: Lyons I (1245)

- 6.1.15 Fourteenth Ecumenical Council: Lyons II (1274)

- 6.1.16 Fifteenth Ecumenical Council: Vienne (1311-1313)

- 6.1.17 Sixteenth Ecumenical Council: Constance (Anitpopes) (1414-1418)

- 6.1.18 Seventeenth Ecumenical Council: Basle/Ferrara/Florence (1431-1439)

- 6.1.19 Eighteenth Ecumenical Council: Lateran V (1512-1517)

- 6.1.20 Nineteenth Ecumenical Council: Trent (1545-1563)

- 6.1.21 Twentieth Ecumenical Council: Vatican I (1869-1870)

- 6.1.22 Twenty-first Ecumenical Council: Vatican II (1962-1965)

- 6.2 Other Heresies

- 6.1 List of Ecumenical Councils

- 7 Marian Doctrine

- 8 History of Lent

- 9 Crusades to the Holy Land

- Bibliography:

1 Background and Definitions

This document reviews history, but mainly in a way to understand the development of the Church’s teachings.

1.1 Church Teachings

What do we mean by Church teachings? These are divided into several areas: Dogma, doctrine, and disciplines.

· Discipline is a practice declared by the Church to help the development of holiness. For instance, the practice of not eating meat on Fridays of lent.

· Doctrine. Doctrine is simply the things that the (Roman Catholic) Church teaches as true. For instance, all the things taught in the catechism, except where otherwise noted, are doctrine of the church.

· Dogma. Dogma is doctrine that has been specifically proclaimed by ecumenical councils or the Pope, acting infallibly. The councils are often called to resolve heresies.

NOTE: Dogma is not created at counsels, it is more fully defined in the face of heresy from the particular doctrine.

1.2 What are Councils

Councils are, then, from their nature, a common effort of the Church, or part of the Church, for self-preservation and self-defense. They appear at her very origin, in the time of the Apostles at Jerusalem, and throughout her whole history whenever faith or morals or discipline are seriously threatened. Although their object is always the same, the circumstances under which they meet impart to them a great variety, which renders a classification necessary. Taking territorial extension for a basis, seven kinds of synods are distinguished. The first three types are defined below.

- Ecumenical Councils are those to which the bishops, and others entitled to vote, are convoked from the whole world under the presidency of the pope or his legates, and the decrees of which, having received papal confirmation, bind all Christians. A council, Ecumenical in its convocation, may fail to secure the approbation of the whole Church or of the pope, and thus not rank in authority with Ecumenical councils. Such was the case with the Robber Synod of 449 (Latrocinium Ephesinum), the Synod of Pisa in 1409, and in part with the Councils of Constance and Basle.

- The second rank is held by the general synods of the East or of the West, composed of but one-half of the episcopate. The Synod of Constantinople (381) was originally only an Eastern general synod, at which were present the four patriarchs of the East (viz. of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem), with many metropolitans and bishops. It ranks as Ecumenical because its decrees were ultimately received in the West also.

- Patriarchal, national, and primatial councils represent a whole patriarchate, a whole nation, or the several provinces subject to a primate.

1.3 What is Heresy and Apostasy

Heresy is defined as: “An opinion or a doctrine at variance with established religious beliefs, especially dissension from or denial of Roman Catholic dogma by a professed believer or baptized church member.” (dictionary.reference.com). New Advent says that heresy is the “Pertinacious adhesion to a doctrine (obstinate adhesion to a particular tenet) contradictory to a point of faith clearly defined by the Church.” Some one doing this is automatically anathema or excommunicated.

Apostasy is defined as leaving the church to go to Judaism, Islam, or paganism. In the early Church this often happened because of persecution.

2 Church Historical Events

This section provides an historical timeline of events in Church history as well as a geographical depiction of the spread of the early Church. The Apostolic Age is highlighted and Ecumenical Counsels are in bold letters.

2.1 Timeline

|

Church History |

Year |

World History |

|

Jesus Christ dies on the Cross Pentecost (NT) |

29 |

Tiberius is Roman Emperor |

|

Council of Jerusalem (NT) |

50 |

|

|

First Persecution: Peter and Paul are martyred (NT) |

65 |

Rome burns. Nero is Emperor |

|

Persecution (NT) |

95 |

Domitian is Emperor |

|

Heresy of Montanism (strict asceticism, judgment) |

172 |

Marcus Aurelius is Emperor |

|

Heresy of Monarchianism (Modalism) |

192 |

Commodus, Septimius Severus |

|

Persecution |

249-251 |

Decius is Emperor. Splits into East and West (2 Augustus,2 Caesar) |

|

Persecution |

284-305 |

Diocletion is Emperor |

|

Edict of Milan establishes religious freedom. Synod of Rome (Donatisism, re-Baptism) |

313 |

Constantine is Emperor |

|

Council of Nicea (Arianism, Creed) |

315 |

|

|

Council of Constantinople I (Macedonius, Pneumatomachians, Creed) |

381 |

|

|

St. Jerome translates the Bible into what is called the Vulgate |

382 |

|

|

|

410 |

Visigoths capture Rome; beginning of dark ages |

|

Council of Ephesus (Theotokos,Nestorianism) |

431 |

|

|

Council of Chalcedon (two natures of Christ) |

451 |

|

|

St Benedict’s rule (western monasticism) |

530 |

|

|

Council of Constantinople II |

553 |

|

|

|

622 |

Foundation of Islam by Mohammed |

|

Council of Constantinople III (Monothelitism) |

680 |

|

|

|

721 |

Spain is overrun by Islam. Battle of Tours – stops Moslem incursion into France |

|

Establishment of Papal States |

756 |

|

|

Council of Nicea II (Iconoclasm, Monophysites) |

787 |

|

|

|

800 |

Charlemagne crowned Emperor of Holy Roman Empire |

|

|

850-1000 |

|

|

Council of Constantinople IV (Photius and Filioque) |

869 |

|

|

Great Schism (Western and Eastern Church |

1054 |

|

|

|

1066 |

William the Conqueror |

|

Church/State conflict over appointing Bishops (Henry IV and Pope Gregory VII) |

1077 |

|

|

First Crusade of Pope Urban II |

1095 |

Crusade |

|

|

1170 |

Church/State conflict murder of Archbishop Thomas Becket |

|

First Lateran Council (Rome) |

1123 |

|

|

Second Lateran Council (Arnold of Brescia) |

1139 |

|

|

Third Lateran Council (Albigenses) |

|

|

|

|

1204 |

Fall of Constantinople to 4th Crusade |

|

Establishment of Dominican and Franciscan religious orders |

1209 |

|

|

Fourth Lateran Council (annual confession and communion, Inquisition) |

1215 |

Magna Carta |

|

Council of Lyons I |

1245 |

Crusade |

|

Council of Lyons II (temporary reunification, Filioque) |

1274 |

|

|

Avignon (“Babylonian Captivity”) |

1304-1377 |

|

|

Council of Vienna |

1311 |

|

|

Council of Constance (antipopes, ecumenical under Martin V) |

1414-1418 |

|

|

Council of Basle/Ferrara/Florence |

1431-1439 |

Gutenberg’s Printing Press. Bible first printed. |

|

|

1453 |

Fall of Constantinople to Islam |

|

|

1492 |

Columbus |

|

Lateran V |

1512-1517 |

Luther post decrees; St Peter’s Basilica is rebuilt under Michelangelo |

|

|

1526 |

Cortez |

|

Guadalupe |

1531 |

|

|

Excommunication of Henry VIII |

1534 |

Henry VIII; establishment of Anglican Church |

|

|

1536 |

Calvin establishes reformed church (Presbyterianism) |

|

Establishment of Jesuits |

1540 |

|

|

Council of Trent (counter-reformation) |

1545-1563 |

|

|

|

1634 |

Maryland established as haven for persecuted Catholics |

|

Missions in California |

1769 |

|

|

|

1775 |

American Revolution |

|

Persecutions in France |

1789 |

French Revolution |

|

Dogma of Immaculate Conception |

1854 |

|

|

Lourdes (St. Bernadette Soubirous) |

1858 |

|

|

Vatican I (infallibility) |

1869-1870 |

|

|

Fatima |

1917 |

World War I, Russian Revolution |

|

Dogma of Assumption of Mary |

1950 |

|

|

Vatican II |

1962-1965 |

|

2.2 Geographic Spread of Early church

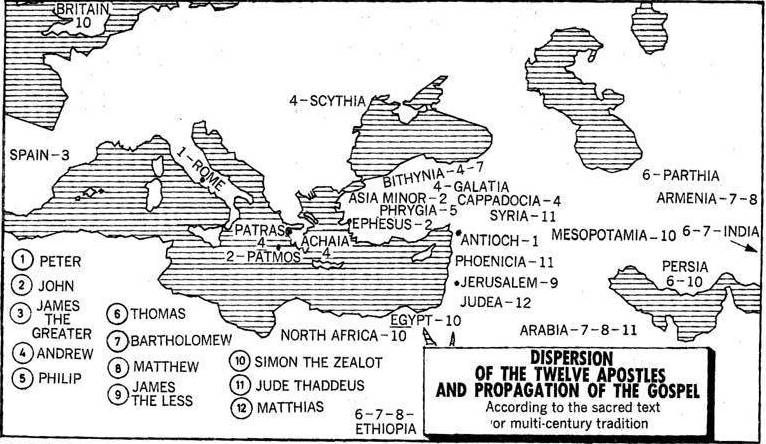

This section shows the geographical spread of the early Church from Jerusalem around the Mediterranean Sea, Europe, Africa and Asia. The first map on the next page is from the New American Bible shows the dispersion of the 12 Apostles. Some of their work is commented in the Acts of the Apostles and some is from tradition.

DISPERSION OF THE TWELVE APOSTLES AND PROPAGATION OF THE GOSPEL. (a) The apostles were twelve men chosen by Jesus to enjoy special jurisdiction and to teach; they were called the Twleve mosl likely after the twelve tribes. (b) The Twelve were alone with him at the Last Supper and they exercised leadership over the early church in Jerusalem. They were the first Bishops and were responsible for spreading Jesus' Gospel. All but Judas were from Galillee, and at least Peter and Philip were married. After Pentecost, they stayed in Palestine until the Holy Spirit drove them to become missionaries. The New Testament only tells of a Peter and Paul, but there is literature describing where they went. All but John was martyred.

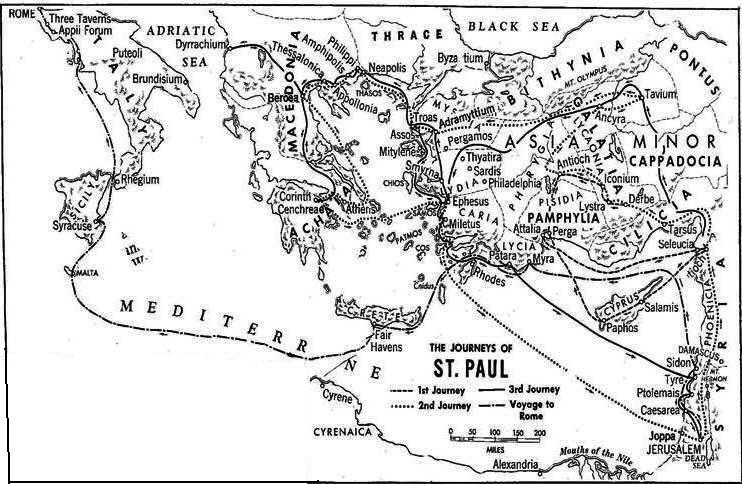

The second picture, also from the New American Bible shows the travels of the Apostle Paul, again from the Acts and tradition.

(a) On his first journey (44-50AD), Paul visits the island of Cyprus, then Pamphylia, Pisidia and Lycaonia, all in Asia Minor, and establishes churches at Pisidian, Antioch, Iconiam and Derbe. After the Apostolic Council of Jerusalem, Paul and Silas (and later Timothry) makes his second mission (50-53AD), first revisiting the churches in Asia Minor and then Galatia. At Troas, Paul has a vision inviting him to preach the Gospel in Macedonia. Paul sails to Europe and preaches in Philippi, Thessalonica, Boroea and then Athens and Corinth. He returned to Antioch by way of Ephesus and Jerusalem. On his third missionary journey (53-58AD), Paul visits nearly the same regions as his second trip, but make Ephesus, where he remains for three years the center of his activity. He plans another journey, intending to leave Jerusalem for Rome and Spain

2.3 Doctrinal Development

A third way to discuss the history of the Catholic Church is to follow its doctrinal development. Most of this document follows that presentation methodology. First we will briefly discuss the formation of the Holy Bible, in particular the New Testament.

Then we will discuss some sample doctrines and their development. We will look at how heresies resulted from early persecution and that doctrine was further developed because of that. Next, we will investigate other heresies that resulted in Church Councils which then further defined doctrine. Finally, the development of Marian doctrine will be discussed.

3 Formulation of Bible

In the New Testament when it refers to Holy Scripture, it refers to the Old Testament, or the Hebrew Scriptures. After the time of the Apostles, the different writings of Apostles or the early followers of the Apostles, writing what they were taught by the Apostles became important to the early Church. Eventually some of these writings became the New Testament.

Note: for a time there was no New Testament, thus the teachings of the Apostles and thus our Lord Jesus Christ were by word only. This is called Sacred Tradition. The conformance of the writings discussed above to this Tradition was largely responsible for their selection as true Revelation from God and their inclusion into the New Testament.

3.1 Old Testament

The Old Testament used was the Greek version called the Septuagint (the “70”). This is traditionally assumed to have been written by Greek speaking Jews in Alexandria between the 3rd Century B.C and about 130 B.C. The Septuagint contains all the books of the Old Testament that are in the current Catholic Bible.

3.2 New Testament

3.2.1 Muratorium Fragment

Named after the man who discoverer it in 1740, this fragmented document dates back to ca. A.D. 170 and is the earliest canonical listing available. Below is the content of the fragment. Note it appears that the first two Gospels are missing, but since it numbers the remaining as three and four, in may be assumed that Matthew and Mark are included. There is also a discussion of some unaccepted books.

Following is the text from the fragment. It is pretty interesting as an early commentary on books that were available.

The third book of the Gospel is that according to Luke.

Luke, the well-known physician, after the ascension of Christ, whom Paul had taken with him as one zealous for the law, composed it in his own name, according to the general belief. Yet he himself had not seen the Lord in the flesh; and therefore, as he was able to ascertain events, so indeed he begins to tell the story from the birth of John.

The fourth of the Gospels is that of John, one of the disciples.

To his fellow disciples and bishops, who had been urging him to write, he said, Fast with me from today to three days, and what will be revealed to each one let us tell it to one another. In the same night it was revealed to Andrew, one of the apostles, that John should write down all things in his own name while all of them should review it. And so, though various elements may be taught in the individual books of the Gospels, nevertheless this makes no difference to the faith of believers, since by the one sovereign Spirit all things have been declared in all the Gospels: concerning the nativity, concerning the passion, concerning the resurrection, concerning life with his disciples, and concerning his twofold coming; the first in lowliness when he was despised, which has taken place, the second glorious in royal power, which is still in the future. What marvel is it then, if John so consistently mentions these particular points also in his epistles, saying about himself, What we have seen with our eyes and heard with our ears and our hands have handled, these things we have written to you? For in this way he professes himself to be not only an eye-witness and hearer, but also a writer of all the marvelous deeds of the Lord, in their order.

Moreover, the acts of all the apostles were written in one book. For "Most excellent Theophilus" Luke compiled the individual events that took place in his presence, as he plainly shows by omitting the martyrdom of Peter as well as the departure of Paul from the city when he journeyed to Spain.

As for the epistles of Paul, they themselves make clear to those desiring to understand, which ones they are, from what place, or for what reason they were sent. First of all, to the Corinthians, prohibiting their heretical schisms; next, to the Galatians, against circumcision; then to the Romans he wrote at length, explaining the plan of the Scriptures, and also that Christ is their principle. It is necessary for us to discuss these one by one, since the blessed apostle Paul himself, following the example of his predecessor John, writes by name to only seven churches in the following sequence: To the Corinthians first, to the Ephesians second, to the Philippians third, to the Colossians fourth, to the Galatians fifth, to the Thessalonians sixth, to the Romans seventh. It is true that he writes once more to the Corinthians and to the Thessalonians for the sake of admonition, yet it is clearly recognizable that there is one Church spread throughout the whole extent of the earth. For John also in the Apocalypse, though he writes to seven churches, nevertheless speaks to all. Paul also wrote out of affection and love one to Philemon, one to Titus, and two to Timothy; and these are held sacred in the esteem of the Church catholic for the regulation of ecclesiastical discipline.

There is current also an epistle to the Laodiceans, and another to the Alexandrians, both forged in Paul's name to further the heresy of Marcion, and several others which cannot be received into the catholic Church. For it is not fitting that gall be mixed with honey.

Moreover, the epistle of Jude and two bearing the name of John are counted in the catholic Church; and the book of Wisdom, written by the friends of Solomon in his honour. We receive only the apocalypses of John and Peter, though some of us are not willing that the latter be read in church. But Hermas wrote "The Shepherd" very recently, in our times, in the city of Rome, while bishop Pius, his brother, was occupying the chair of the church of the city of Rome. And therefore it ought indeed to be read; but it cannot be read publicly to the people in church either among the Prophets, whose number is complete, or among the Apostles, for it is after their time.

But we accept nothing whatever of Arsinous or Valentinus or Miltiades, who also composed a new book of psalms for Marcion, together with Basilides, the Asian founder of the Cataphrygians...

3.2.2 Eusebius

Eusebius described what he considered the canon of the New Testament in the year 250. The following is an excerpt of his description of these texts from Church History:Book III, Chapter 25 The Divine Scriptures that are accepted and those that are not.

Since we are dealing with this subject it is proper to sum up the writings of the New Testament which have been already mentioned. First then must be put the holy quaternion of the Gospels; following them the Acts of the Apostles. After this must be reckoned the epistles of Paul; next in order the extanfinal former epistle of John, and likewise the epistle of Peter, must be maintained. After them is to be placed, if it really seem proper, the Apocalypse of John, concerning which we shall give the different opinions at the proper time. These then belong among the accepted writings. Among the disputed writings, which are nevertheless recognized by many, are extant the so-called epistle of James and that of Jude, also the second epistle of Peter, and those that are called the second and third of John, whether they belong to the evangelist or to another person of the same name. Among the rejected writings must be reckoned also the Acts of Paul, and the so-called Shepherd, and the Apocalypse of Peter, and in addition to these the extant epistle of Barnabas, and the so-called Teachings of the Apostles (Didache); and besides, as I said, the Apocalypse of John, if it seem proper, which some, as I said, reject, but which others class with the accepted books. And among these some have placed also the Gospel according to the Hebrews, with which those of the Hebrews that have accepted Christ are especially delighted. And all these may be reckoned among the disputed books. But we have nevertheless felt compelled to give a catalogue of these also, distinguishing those works which according to ecclesiastical tradition are true and genuine and commonly accepted, from those others which, although not canonical but disputed, are yet at the same time known to most ecclesiastical writers -- we have felt compelled to give this catalogue in order that we might be able to know both these works and those that are cited by the heretics under the name of the apostles, including, for instance, such books as the Gospels of Peter, of Thomas, of Matthias, or of any others besides them, and the Acts of Andrew and John and the other apostles, which no one belonging to the succession of ecclesiastical writers has deemed worthy of mention in his writings. And further, the character of the style is at variance with apostolic usage, and both the thoughts and the purpose of the things that are related in them are so completely out of accord with true orthodoxy that they clearly show themselves to be the fictions of heretics. Wherefore they are not to be placed even among the rejected writings, but are all of them to be cast aside as absurd and impious. Let us now proceed with our history.

3.3 St Jerome

Around the year 382 A.D., St Jerome undertook the translation of the Greek Bible at the time into the common language, or Latin. This translation became known as the Vulgate. St. Jerome made use of the original language texts (Hebrew, Aramaic, Greek) as much as possible. There was debate about including books that did not have original language available, but all the books in the canon were translated and the translation contained exactly the books that are in the current Catholic Bible.

4 Doctrinal Development

This section shows examples of the development of some early doctrines. These examples include:

- Eucharist

- Jesus, Son of God

- Trinity

4.1 Eucharist

The following is from the First Apology of St. Justin Martyr, Chapter 66. He lived from around 100AD to 165AD. This is in the living memory of the Apostles themselves. Clearly our present understanding of the Eucharist is nearly identical.

4.1.1 Justin Martyr (b100, converted 130, d165)

4.1.2 Divine Liturgy (Mass)

From Justin Martyr , 1st apology (~150) , Didiche (~100), First Epistle of Clement to the Corinthians (~95), Apostolic Constitutions, chapter 8 (5th Century) we find the outline of the early Mass.

1. Lessons

2. Sermon by the bishop

3. Prayers for all people

4. Kiss of peace

5. Offertory of bread and wine and water brought up by the deacons

6. Thanksgiving-prayer by the bishop

7. Consecration by the words of institution

8. Intercession for the people

9. The people end this prayer with Amen

10. Communion

4.1.3 Lateran IV

The council affirmed the dogma of transubstantiation. This was stated strongly in 1050 AD by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Lanfranc while he was on business in Rome. This term comes from Lanfranc. Transubstantiation refers to occidents (substance) and accidents (appearance). In transubstantiation, the occidents of wheat made bread is changed to the body (flesh) of Christ and the occidents of the fermented grape wine is changed to the blood of Christ.

This council also required all believers to receive Eucharist at least once a year and go to confession yearly.

4.2 Jesus, “the Son of God” is God

The heresy of Monarchianism (Sabellianism), 3rd century, denied the Trinity as three divine persons, thus that Jesus was the Son of God, a person distinct from the Father.

The heresy of Arianism, 4th century, denied that Christ shared the divinity of the Father. He is a created being superior to all other created beings, but not one in substance with the Father. The Council of Nicea stated very clearly that Arianism is heresy. Jesus is a divine person, one in substance with the Father. The Creed of Nicea clearly states this. Note that this is not the creation of this doctrine, but the refutation of the heresy of Arianism.

Monophysitism denied that Christ has both a human and divine nature and Monothelitism refined this to denying that Christ has both a human will and a divine will. The third council of Constantinople refutes this.

4.3 Trinity

As in the section above, Monarchianism denies the Trinity as three Divine Persons, only that Jesus and the Holy Spirit are merely different powers of the one Divine Person, the Father. Likewise, Arianism denies the Trinity as it denies that Jesus is one in substance with the Father.

The later heresy of the Pneumatomachians denies that the Holy Spirit is Divine, thus again denying the Trinity. The first Council of Constantinople refuted this heresy.

5 Persecution

The early Church underwent much persecution and martyrdom. Here are some examples of the most egregious periods. The persecution ended with the Edict of Milan (313) when Constantine was emperor. Note, that Heresies often arose from the bouts of persecution, resulting in the further development of doctrine.

NOTE: in all of the persecution, no Pope ever apostatized.

5.1 Nero (64-67)

· Rome burns, Christians blamed by Nero

· Christianity declared a capital offence (until Edict of Milan, 313)

· Peter and Paul martyred (67)

· NOTE: Jerusalem destroyed, including Temple (70)

5.2 Domitian (95)

Persecution was again empire wide.

5.3 Local Martyrdoms

For a long time after Domitian (until Decius), even though it remained a capital offense to be Christian, most persecution was local as for example in Lyon then called Lugdunum(177). This was the worst persecution since Nero. During this time the heresy of Montanism existed. According to this heresy, those who denied Christ, thus becoming apostate, were not to be accepted again.

5.3.1.1 Heresy of Montanism

Apocalyptic movement of the 2nd century. It arose in Phrygia (c.172) under the leadership of a certain Montanus and two female prophets, Prisca and Maximillia, whose entranced utterances were deemed oracles of the Holy Spirit. They had an immediate expectation of Judgment Day, and they encouraged ecstatic prophesying and strict asceticism. They believed that a Christian fallen from grace could never be redeemed, in opposition to the Catholic view that, since the sinner’s contrition restored him to grace, the church must receive him again. Montanism antagonized the church because the sect claimed a superior authority arising from divine inspiration. Catholics were told that they should flee persecution, Montanists were told to seek it. When the Montanists began to set up a hierarchy of their own, the Catholic leaders, fearing to lose the cohesion essential to the survival of persecuted Christianity, denounced the movement. Tertullian was a notable member of the movement, which died (c.220) as a sect, except in isolated areas of Phrygia, where it continued to the 7th cent. But the puristic anti-intellectual movement had many descendants—Novatian, the Donatists (see Donatism), the Cathari, and even Emanuel Swedenborg and Edward Irving.

5.4 Decius (250)

· Proclamation to make public sacrifice to idols on pain of death

· Began by killing Pope Fabian

· Many bishops and others killed in only four months before Decius disappears in battle against the Goths.

5.5 Valerian (258-259)

· First orders all Bishops to leave their Sees

· Next orders all Bishops, Priests and Deacons to be put to death

· Desired the “wealth” of the Church to use in battle

· Pope Sixtus and St. Lawrence (“turn me over”) are martyred

· Tarsicius was martyred while protecting the Eucharist which he was carrying to a home.

5.6 Diocletian and Galerius (303-311)

· Start against Church possessions and property and prohibition against Christians holding public office or freeing Christian slaves

· Idol sacrifice or die

· Diocletian collapses and Galerius removes all restraint and full blown persecutions entails

· 304 AD becomes worst year since Calvary

6 Councils and Heresies

Recall that Doctrine is not created at councils; it is more fully defined in the face of heresy from the particular doctrine.

6.1 List of Ecumenical Councils

6.1.1 Council of Jerusalem

The Council of Jerusalem decided that one did not first need to become Jewish before becoming Christian. This is described in the Acts of the Apostles. Part of the reason for the council was because Paul was baptizing gentiles without first converting them to Judaism. St. Peter decreed that this was ok, that anything else was an undue burden.

6.1.2 First Ecumenical Council: Nicea I (Arianism,Gnosticism) (325)

The Council of Nicea lasted two months and twelve days. Three hundred and eighteen bishops were present. Hosius, Bishop of Cordova, assisted as legate of Pope Sylvester. The Emperor Constantine was also present. To this council we owe The Creed (Symbolum) of Nicea, defining against Arius the true Divinity of the Son of God (homoousios), and the fixing of the date for keeping Easter (against the Quartodecimans).

6.1.2.1 Heresy of Gnosticism

A collective name for a large number of greatly-varying and pantheistic-idealistic sects, which flourished from some time before the Christian Era down to the fifth century, and which, while borrowing the phraseology and some of the tenets of the chief religions of the day, and especially of Christianity, held matter to be a deterioration of spirit, and the whole universe a depravation of the Deity, and taught the ultimate end of all being to be the overcoming of the grossness of matter and the return to the Parent-Spirit, which return they held to be inaugurated and facilitated by the appearance of some God-sent Saviour. The means of acquiring this salvation is usually through some secret knowledge (to which the word Gnostic is related). Thus the holder of this secret knowledge often finds this salvation merely by having the knowledge.

6.1.2.2 Heresy of Arianism

A heresy which arose in the fourth century (Arius), and denied the Divinity of Jesus Christ. The drift of all he advanced was this: to deny that in any true sense God could have a Son; as Mohammed tersely said afterwards, "God neither begets, nor is He begotten" (Koran, 112). We have learned to call that denial Unitarianism. It was the ultimate scope of Arian opposition to what Christians had always believed. But the Arian, though he did not come straight down from the Gnostic, pursued a line of argument and taught a view which the speculations of the Gnostic had made familiar. He described the Son as a second, or inferior God, standing midway between the First Cause and creatures; as Himself made out of nothing, yet as making all things else; as existing before the worlds of the ages; and as arrayed in all divine perfections except the one which was their stay and foundation. God alone was without beginning, unoriginate; the Son was originated, and once had not existed. For all that has origin must begin to be.

Such is the genuine doctrine of Arius. Using Greek terms, it denies that the Son is of one essence, nature, or substance with God; He is not consubstantial (homoousios) with the Father, and therefore not like Him, or equal in dignity, or co-eternal, or within the real sphere of Deity. The Logos which St. John exalts is an attribute, Reason, belonging to the Divine nature, not a person distinct from another, and therefore is a Son merely in figure of speech. These consequences follow upon the principle which Arius maintains in his letter to Eusebius of Nicomedia, that the Son "is no part of the Ingenerate." Hence the Arian sectaries who reasoned logically were styled Anomoeans: they said that the Son was "unlike" the Father. And they defined God as simply the Unoriginate. They are also termed the Exucontians (ex ouk onton), because they held the creation of the Son to be out of nothing.

6.1.3 Second Ecumenical Council: Constantinople I (Macedonianism, Pneumatotomachianism) (381)

The First General Council of Constantinople, under Pope Damasus and the Emperor Theodosius I, was attended by 150 bishops. It was directed against the followers of Macedonius, who impugned the Divinity of the Holy Ghost. To the above-mentioned Nicene Creed it added the clauses referring to the Holy Ghost (qui simul adoratur) and all that follows to the end.

6.1.3.1 Heresies of Macedonianism and Pneumatomachians

Denial of the Divinity of the Holy Spirit. Heresy (thought to be taught by Macedonius) declaring the Holy Ghost a mere creature and a ministering angel.

6.1.4 Third Ecumenical Council: Ephesus (Nestorianism) (431)

The Council of Ephesus, of more than 200 bishops, presided over by St. Cyril of Alexandria representing Pope Celestine I, defined the true personal unity of Christ, declared Mary the Mother of God (theotokos) against Nestorius, Bishop of Constantinople, and renewed the condemnation of Pelagius.

6.1.4.1 Heresy of Nestorianism

Nestorius was a disciple of the school of Antioch, and his Christology was essentially that of Diodorus of Tarsus and Theodore of Mopsuestia, both Cilician bishops and great opponents ofArianism. Both died in the Catholic Church. Diodorus was a holy man, much venerated by St. John Chrysostom. Theodore, however, was condemned in person as well as in his writings by the Fifth General Council, in 553. In opposition to many of the Arians, who taught that in the Incarnation the Son of God assumed a human body in which His Divine Nature took the place of soul, and to the followers of Apollinarius of Laodicea, who held that the Divine Nature supplied the functions of the higher or intellectual soul, the Antiochenes insisted upon the completeness of the humanity which the Word assumed. Unfortunately, they represented this human nature as a complete man, and represented the Incarnation as the assumption of a man by the Word. The same way of speaking was common enough in Latin writers (assumere hominem, homo assumptus) and was meant by them in an orthodox sense; we still sing in the Te Deum: "Tu ad liberandum suscepturus hominem", where we must understand "ad liberandum hominem, humanam naturam suscepisti". But the Antiochene writers did not mean that the "man assumed" (ho lephtheis anthropos) was taken up into one hypostasis with the Second Person of the Holy Trinity. They preferred to speak of synapheia, "junction", rather than enosis, "unification", and said that the two were one person in dignity and power, and must be worshipped together. The word person in its Greek form prosopon might stand for a juridical or fictitious unity; it does not necessarily imply what the word person implies to us, that is, the unity of the subject of consciousness and of all the internal and external activities. Hence we are not surprised to find that Diodorus admitted two Sons, and that Theodore practically made two Christs, and yet that they cannot be proved to have really made two subjects in Christ. Two things are certain: first, that, whether or not they believed in the unity of the subject in the Incarnate Word, at least they explained that unity wrongly; secondly, that they used most unfortunate and misleading language when they spoke of the union of the manhood with the Godhead -- language which is objectively heretical, even were the intention of its authors good.

6.1.4.2 Heresy of Pelagianism

Pelagius lived during the end of the fourth century into the fifth century. Little is known about him, aside from his heresy and that he seems to have been born in what is today Great Britain. Pelagianism was declared a heresy around the beginning of the fifth century. It was denounced by Saint Augustine among others. Augustine and others then began developing the doctrines of Original Sin and the necessity of Baptism for salvation.

Here is a brief outline of Pelagianism,

- Even if Adam had not sinned, he would have died.

- Adam's sin harmed only himself, not the human race.

- Children just born are in the same state as Adam before his fall.

- The whole human race neither dies through Adam's sin or death, nor rises again through the resurrection of Christ.

- The (Mosaic Law) is as good a guide to heaven as the Gospel.

- Even before the advent of Christ there were men who were without sin.

6.1.5 Fourth Ecumenical Council: Chalcedon (Monphysitism) (451)

The Council of Chalcedon -- 150 bishops under Pope Leo the Great and the Emperor Marcian -- defined the two natures (Divine and human) in Christ against Eutyches, who was excommunicated.

6.1.5.1 Heresy of Monophysitism

Monophysitism is the denial of the two natures of Christ, Divine and Human. Catholic doctrine is that Christ is one person, with two natures. Denying that Christ has a human nature denies that as in one man all have fallen, so in another man, Christ, all are redeemed.

6.1.6 Fifth Ecumenical Council: Constantinople II (553)

The Second General Council of Constantinople, of 165 bishops under Pope Vigilius and Emperor Justinian I, condemned the errors of Origen and certain writings (The Three Chapters) of Theodoret, of Theodore, Bishop of Mopsuestia and of Ibas, Bishop of Edessa; it further confirmed the first four general councils, especially that of Chalcedon whose authority was contested by some heretics.

6.1.7 Sixth Ecumenical Council: Constantinople III (Monothelitism) (680-681)

The Third General Council of Constantinople, under Pope Agatho and the Emperor Constantine Pogonatus, was attended by the Patriarchs of Constantinople and of Antioch, 174 bishops, and the emperor. It put an end to Monothelitism by defining two wills in Christ, the Divine and the human, as two distinct principles of operation. It anathematized Sergius, Pyrrhus, Paul, Macarius, and all their followers.

6.1.7.1 Heresy of Monothelitism

Denial of the two wills of Christ, Divine and Human. This is a modification of Monophysitism. Again, denying that Christ has a human will denies that as in one man all have fallen, so in another man, Christ, all are redeemed. Christ was fully human, in body, nature and will.

6.1.8 Seventh Ecumenical Council: Nicea II (Iconoclasm) (787)

The Second Council of Nicea was convoked by Emperor Constantine VI and his mother Irene, under Pope Adrian I, and was presided over by the legates of Pope Adrian; it regulated the veneration of holy images. Between 300 and 367 bishops assisted.

6.1.8.1 Heresy of Iconoclasm

This heresy is the condemnation of the use of statues and pictures in churches and elsewhere. It may have been aided by the rise of Islam and that religion’s rejection of any images. It occurred in two stages, first in the seventh century during the time of Pope Gregory II. He answered in 727, by a long defense of the pictures. He explains the difference between them and idols, with some surprise that Emperor Leo does not already understand it. He describes the lawful use of, and reverence paid to, pictures by Christians. He blames the emperor's interference in ecclesiastical matters and his persecution of image-worshippers. A council is not wanted; all Leo has to do is to stop disturbing the peace of the Church. Even after this response from the pope, Iconoclasm continued with destruction of images and persecution of those who would not destroy them. This caused schism between Rome and Constantinople.

The second part took place in the eighth century. The Empress Irene was regent for her young son and was trying to reverse the affects of Iconoclasm. Nevertheless, Iconoclasm continued and finally a council was called to deal with it.

6.1.9 Eighth Ecumenical Council: Constantinople IV (869)

The Fourth General Council of Constantinople, under Pope Adrian II and Emperor Basil numbering 102 bishops, 3 papal legates, and 4 patriarchs, consigned to the flames the Acts of an irregular council (conciliabulum) brought together by Photius against Pope Nicholas and Ignatius the legitimate Patriarch of Constantinople; it condemned Photius who had unlawfully seized the patriarchal dignity. The Photian Schism, however, triumphed in the Greek Church, and no other general council took place in the East.

6.1.10 Ninth Ecumenical Council: Lateran I (1123)

The First Lateran Council, the first held at Rome, met under Pope Callistus II. About 900 bishops and abbots assisted. It abolished the right claimed by lay princes, of investiture with ring and crosier to ecclesiastical benefices and dealt with church discipline and the recovery of the Holy Land from the infidels.

6.1.11 Tenth Ecumenical Council: Lateran II (1139)

The Second Lateran Council was held at Rome under Pope Innocent II, with an attendance of about 1000 prelates and the Emperor Conrad. Its object was to put an end to the errors of Arnold of Brescia.

6.1.12 Eleventh Ecumenical Council: Lateran III (1179)

The Third Lateran Council took place under Pope Alexander III, Frederick I being emperor. There were 302 bishops present. It condemned the Albigenses and Waldenses and issued numerous decrees for the reformation of morals.

6.1.13 Twelfth Ecumenical Council: Lateran IV (Albigensianism) (1215)

The Fourth Lateran Council was held under Innocent III. There were present the Patriarchs of Constantinople and Jerusalem, 71 archbishops, 412 bishops, and 800 abbots the Primate of the Maronites, and St. Dominic. It issued an enlarged creed (symbol) against the Albigenses (Firmiter credimus), condemned the Trinitarian errors of Abbot Joachim, and published 70 important reformatory decrees. This is the most important council of the Middle Ages, and it marks the culminating point of ecclesiastical life and papal power. Other important ideas that were reaffirmed are yearly confession and the Easter Duty.

6.1.13.1 Heresy of Albigensianism

The Albigenses asserted the co-existence of two mutually opposed principles, one good, and the other evil. The former is the creator of the spiritual, the latter of the material world. The bad principle is the source of all evil; natural phenomena, either ordinary like the growth of plants, or extraordinary as earthquakes, likewise moral disorders (war), must be attributed to him. He created the human body and is the author of sin, which springs from matter and not from the spirit. The Old Testament must be either partly or entirely ascribed to him; whereas the New Testament is the revelation of the beneficent God. The latter is the creator of human souls, which the bad principle imprisoned in material bodies after he had deceived them into leaving the kingdom of light. This earth is a place of punishment, the only hell that exists for the human soul. Punishment, however, is not everlasting; for all souls, being Divine in nature, must eventually be liberated. To accomplish this deliverance God sent upon earth Jesus Christ, who, although very perfect, like the Holy Ghost, is still a mere creature. The Redeemer could not take on a genuine human body, because he would thereby have come under the control of the evil principle. His body was, therefore, of celestial essence, and with it He penetrated the ear of Mary. It was only apparently that He was born from her and only apparently that He suffered. His redemption was not operative, but solely instructive. To enjoy its benefits, one must become a member of the Church of Christ (the Albigenses). Here below, it is not the Catholic sacraments but the peculiar ceremony of the Albigenses known as the consolamentum, or "consolation," that purifies the soul from all sin and ensures its immediate return to heaven. The resurrection of the body will not take place, since by its nature all flesh is evil.

We see here the synthesis of several previous heresies, Gnosticism, Sabellianism and Arianism.

6.1.14 Thirteenth Ecumenical Council: Lyons I (1245)

The First General Council of Lyons was presided over by Innocent IV; the Patriarchs of Constantinople, Antioch, and Aquileia (Venice), 140 bishops, Baldwin II, Emperor of the East, and St. Louis, King of France, assisted. It excommunicated and deposed Emperor Frederick II and directed a new crusade, under the command of St. Louis, against the Saracens and Mongols.

6.1.15 Fourteenth Ecumenical Council: Lyons II (1274)

The Second General Council of Lyons was held by Pope Gregory X, the Patriarchs of Antioch and Constantinople, 15 cardinals, 500 bishops, and more than 1000 other dignitaries. It effected a temporary reunion of the Greek Church with Rome. The word filioque was added to the symbol of Constantinople and means were sought for recovering Palestine from the Turks. It also laid down the rules for papal elections. (The symbol of Constantinople is the Creed of Constantinople, the one we say at Mass.

The filoque is the phrase “and the son”, as in “who proceeds from the Father and the Son.”

6.1.16 Fifteenth Ecumenical Council: Vienne (1311-1313)

The Council of Vienne was held in that town in France by order of Clement V, the first of the Avignon popes. The Patriarchs of Antioch and Alexandria, 300 bishops (114 according to some authorities), and 3 kings -- Philip IV of France, Edward II of England, and James II of Aragon -- were present. The synod dealt with the crimes and errors imputed to the Knights Templars, the Fraticelli, the Beghards, and the Beguines, with projects of a new crusade, the reformation of the clergy, and the teaching of Oriental languages in the universities.

6.1.17 Sixteenth Ecumenical Council: Constance (Anitpopes) (1414-1418)

The Council of Constance was held during the great Schism of the West, with the object of ending the divisions in the Church. It became legitimate only when Gregory XI had formally convoked it. Owing to this circumstance it succeeded in putting an end to the schism by the election of Pope Martin V, which the Council of Pisa (1403) had failed to accomplish on account of its illegality. The rightful pope confirmed the former decrees of the synod against Wyclif and Hus. This council is thus ecumenical only in its last sessions (XLII-XLV inclusive) and with respect to the decrees of earlier sessions approved by Martin V.

6.1.18 Seventeenth Ecumenical Council: Basle/Ferrara/Florence (1431-1439)

The Council of Basle met first in that town, Eugene IV being pope, and Sigismund Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. Its object was the religious pacification of Bohemia. Quarrels with the pope having arisen, the council was transferred first to Ferrara (1438), then to Florence (1439), where a short-lived union with the Greek Church was effected, the Greeks accepting the council's definition of controverted points. The Council of Basle is only ecumenical till the end of the twenty-fifth session, and of its decrees Eugene IV approved only such as dealt with the extirpation of heresy, the peace ofChristendom, and the reform of the Church, and which at the same time did not derogate from the rights of the Holy See. (See also the Council of Florence.)

6.1.19 Eighteenth Ecumenical Council: Lateran V (1512-1517)

The Fifth Lateran Council sat from 1512 to 1517 under Popes Julius II and Leo X, the emperor being Maximilian I. Fifteen cardinals and about eighty archbishops and bishops took part in it. Its decrees are chiefly disciplinary. A new crusade against the Turks was also planned, but came to naught, owing to the religious upheaval in Germany caused by Luther.

6.1.20 Nineteenth Ecumenical Council: Trent (1545-1563)

The Council of Trent lasted eighteen years (1545-1563) under five popes: Paul III, Julius III, Marcellus II, Paul IV and Pius IV, and under the Emperors Charles V and Ferdinand. There were present 5 cardinal legates of the Holy See, 3 patriarchs, 33 archbishops, 235 bishops, 7 abbots, 7 generals of monastic orders, and 160 doctors of divinity. It was convoked to examine and condemn the errors promulgated by Luther and other Reformers, and to reform the discipline of the Church. Of all councils it lasted longest, issued the largest number of dogmatic and reformatory decrees, and produced the most beneficial results.

6.1.21 Twentieth Ecumenical Council: Vatican I (1869-1870)

The Vatican Council was summoned by Pius IX. It met 8 December, 1869, and lasted till 18 July, 1870, when it was adjourned; it is still (1908) unfinished. There were present 6 archbishop-princes, 49 cardinals, 11 patriarchs, 680 archbishops and bishops, 28 abbots, 29 generals of orders, in all 803. Besides important canons relating to the Faith and the constitution of the Church, the council decreed the infallibility of the pope when speaking ex cathedra, i.e. when as shepherd and teacher of all Christians, he defines a doctrine concerning faith or morals to be held by the whole Church.

6.1.22 Twenty-first Ecumenical Council: Vatican II (1962-1965)

Vatican II was called by Pope John XXIII. It was

attended at various times by 2,100 to 2,300 Bishops from all over the

world and for the first time, non-Catholic observers were invited.

Seventeen Orthodox Churches and Protestant denominations sent

observers. More than three dozen representatives of other Christian

communities were present at the opening session, and the number grew to

nearly 100 by the end of the 4th Council Period. It did not declare any

dogma. Listed below are the major documents that came from this

council.

Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy (Sacrosanctum Concilium) 12/4/1963 sought

to adapt more closely to the needs of our age those institutions which

are subject to change, to foster Christian reunion, and to strengthen

the Church's evangelization.

Decree on the Media (Inter Mirifica)

12/4/1963 defined the modern means of communication as those which can

reach not only single individuals but even the whole of human society.

It declared that the content of the media must be true, and - within

the limits of justice and charity - complete.

Dogmatic Constitution on the Church (Lumen Gentium)

12/4/1963 explained the Church's nature as a sign and instrument of

communion with God and of unity among men. It also clarified the

Church's mission as the universal sacrament of salvation.

Decree on the Catholic Eastern Churches (Orientalium Ecclesiarum)

11/21/1964 encouraged Eastern Catholics to remain faithful to their

ancient traditions, reassured them that their distinctive privileges

would be respected, and urged closer ties with the separated Eastern

churches, with a view to fostering Christian unity.

Decree on Ecumenism (Unitatis Redintegratia)

11/21/1965 made a careful distinction between spiritual ecumenism,

mainly prayer and the practice of virtue, and practical ecumenism,

which actively fosters Christian reunion.

Decree on the Pastoral Office of Bishops (Christus Dominus)

10/28/1965 urged bishops to cooperate with one another and with the

Bishop of Rome and to decide on effective means for using the modern

means of communication.

Decree on the Renewal of Religious Life (Perfectae Caritatis)

10/28/1965 set down norms for spiritual renewal and prudent adaptation,

legislating community life under superiors, corporate prayer, poverty

of sharing, distinctive religious habit, and continued spiritual and

doctrinal education.

Decree on the Training of Priests (Optatam Totius)

10/28/1965 centered on fostering vocations, giving more attention to

spiritual formation, preparing for pastoral work and developing priests

with a filial attachment to the Vicar of Christ, and loyal cooperation

with their bishops and fellow priests.

Declaration on Christian Education (Gravissimum Educationis)

10/28/1965 told all Christians that they have a right to a Christian

education, reminded parents they have the primary right and duty to

teach their children, and warned believers of the dangers of state

monopoly in education.

Declaration on the Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions (Nostra Aetate)

10/28/1965 urged Catholics to enter, with prudence and charity, into

discussion and collaboration with members of other religions.

Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation (Dei Verbum)

11/18/1965 distinguished Sacred Scripture from Sacred Tradition,

declared that the Bible must be interpreted under the Church's

guidance, and explained how development of doctrine is the Church's

ever-deeper understanding of what God has once and for all revealed to

the human race.

Decree on the Apostolate of the Laity (Apostolicam Actuositatem)

11/18/1965 is a practical expression of the Church's mission, to which

the laity are specially called in virtue of their Baptism and

incorporation into Christ. It recognizes that the laity have the right

to establish and direct their own associations, on the condition that

they preserve the necessary link with ecclesiastical authority.

Declaration on Religious Liberty (Dignitatis Humanae)

12/7/1965 affirms each person's liberty to believe in God and worship

Him according to one's conscience and reaffirms the Catholic Church's

revealed freedom for herself and before every public authority.

Decree on the Church's Missionary Activity (Ad Gentes Divinitus)

12/7/1965 defines evangelization as the implanting of the Church among

peoples in which she has not yet taken root. It urges even the young

churches to engage in evangelization as soon as possible and stresses

the importance of adequate training of missionaries and their sanctity

of life.

Decree on the Ministry and Life of Priests (Presbyterorum Ordinis)

12/7/1965 defines priests as men who are ordained to offer the

Eucharistic Sacrifice, forgive sins in Christ's name, and exercise the

priestly office on behalf of others in the name of Christ. Priestly

celibacy is reaffirmed, and priestly sanctity declared to be essential.

Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes)

12/7/1965 identifies atheism as one of the most serious problems of our

times, gives the most extensive treatment of marriage and the family in

conciliar history, and declares the Church's strong position on war and

peace in the nuclear age.

6.2 Other Heresies

This section lists some other heresies that resulted in useful doctrinal development.

6.2.1 Monarchianism or Sabellianism

These are related heresies, Monarchianism first in the second century and later Sabellianism. Monarchiasts went so far as to say that the Father came down as the Son to die. Sabellius, a presbyter of Ptolemais in the third century, refined this and maintained that there is but one person in the Godhead, and that the Son and Holy Spirit are only different powers, operations, or offices of the one God the Father. This is sometimes called modalism (The Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit are modes of God).

6.2.2 Manichæism

Manichæism is a religion founded by the Persian Mani in the latter half of the third century. It purported to be the true synthesis of all the religious systems then known, and actually consisted of Zoroastrian Dualism, Babylonian folklore, Buddhist ethics, and some small and superficial, additions of Christian elements. As the theory of two eternal principles, good and evil, is predominant in this fusion of ideas and gives color to the whole, Manichæism is classified as a form of religious Dualism (often, there are two gods, or two sides of god, a good side and an evil side). It spread with extraordinary rapidity in both East and West and maintained a sporadic and intermittent existence in the West (Africa, Spain, France, North Italy, the Balkans) for a thousand years, but it flourished mainly in the land of its birth, (Mesopotamia, Babylonia, Turkistan) and even further East in Northern India, Western China, and Tibet, where, c. A.D. 1000, the bulk of the population professed its tenets and where it died out at an uncertain date.

6.2.3 Donatists - time of Constantine

Schismatic movement among Christians of N Africa (fl. 4th cent.), led by Donatus, bishop of Casae Nigrae (fl. 313), and the theologian Donatus the Great or Donatus Magnus (d. 355). The schism arose when certain Christians protested the election of the bishop of Carthage, charging that his consecration by Felix, bishop of Aptunga, was invalid because Felix was considered a traditor (i.e., one who turns over sacred books and relics to the civil authorities during a persecution). Condemnation was extended to all in communion with Felix. Behind their objection lay the heresy, familiar to Montanism and Novatian, that only those living a blameless life belonged in the church, and, further, that the validity of any sacrament depended upon the personal worthiness of the priest administering it. The Donatist practice of rebaptizing was particularly abhorrent to the orthodox. Condemned by the Synod of Arles (314) and also by the Roman emperor, Constantine I, the Donatists seceded (316) and set up their own hierarchy. By 350 they outnumbered the orthodox Christians in Africa, and each city had its opposing orthodox and Donatist bishops. It was the teaching of St. Augustine, as presented in his writings and at the debate between orthodox and Donatist bishops at Carthage (411), that turned the tide against Donatism. Strong state suppression and ascetic excesses among some of their own members further reduced their number. The remnants of the schismatic movement had vanished along with African Christianity before the advent of the Islamic invaders.

7 Marian Doctrine

From New Advent:

7.1 Immaculate Conception

Patristic writings on Mary's purity abound.

- The Fathers call Mary the tabernacle exempt from defilement and corruption (Hippolytus, "Ontt. in illud, Dominus pascit me");

- Origen (185-232) calls her worthy of God, immaculate of the immaculate, most complete sanctity, perfect justice, neither deceived by the persuasion of the serpent, nor infected with his poisonous breathings ("Hom. i in diversa");

- Ambrose (340-397) says she is incorrupt, a virgin immune through grace from every stain of sin ("Sermo xxii in Ps. cxviii);

- Maximum of Turin calls her a dwelling fit for Christ, not because of her habit of body, but because of original grace ("Nom. viii de Natali Domini");

- Theodotus of Ancyra (~300) terms her a virgin innocent, without spot, void of culpability, holy in body and in soul, a lily springing among thorns, untaught the ills of Eve nor was there any communion in her of light with darkness, and, when not yet born, she was consecrated to God ("Orat. in S. Dei Genitr.").

- In refuting Pelagius St. Augustine (354-430) declares that all the just have truly known of sin "except the Holy Virgin Mary, of whom, for the honour of the Lord, I will have no question whatever where sin is concerned" (De naturâ et gratiâ 36).

- Mary was pledged to Christ (Peter Chrysologus (406-450), "Sermo cxl de Annunt. B.M.V.");

- “it is evident and notorious that she was pure from eternity, exempt from every defect “ (Typicon S. Sabae);

- “she was formed without any stain” (St. Proclus (~440), "Laudatio in S. Dei Gen. ort.", I, 3);

- “when the Virgin Mother of God was to be born of Anne, nature did not dare to anticipate the germ of grace, but remained devoid of fruit” (John Damascene, "Hom. i in B. V. Nativ.", ii).

- The Syrian Fathers never tire of extolling the sinlessness of Mary. St. Ephraem (~350) considers no terms of eulogy too high to describe the excellence of Mary's grace and sanctity: "Most holy Lady, Mother of God, alone most pure in soul and body, alone exceeding all perfection of purity ...., alone made in thy entirety the home of all the graces of the Most Holy Spirit, and hence exceeding beyond all compare even the angelic virtues in purity and sanctity of soul and body . . . . my Lady most holy, all-pure, all-immaculate, all-stainless, all-undefiled, all-incorrupt, all-inviolate spotless robe of Him Who clothes Himself with light as with a garment . ... flower unfading, purple woven by God, alone most immaculate" ("Precationes ad Deiparam" in Opp. Graec. Lat., III, 524-37).

- To St. Ephraem she was as innocent as Eve before her fall, a virgin most estranged from every stain of sin, more holy than the Seraphim, the sealed fountain of the Holy Ghost, the pure seed of God, ever in body and in mind intact and immaculate ("Carmina Nisibena").

7.2 Perpetual Virginity

The doctrine of Mary’s perpetual virginity is, “Mary was a virgin before, during and forever after the conception and birth of Jesus”.

St. Jerome (4th Century), “De perpetua Virginitate B. Mariae; adversus Helvidium.” Helvidius maintained that the mention in the Gospels of the "sisters" and "brethren" of our Lord was proof that the Blessed Virgin had subsequent issue, and he supported his opinion by the writings of Tertullian and Victorinus. The outcome of his views was that virginity was ranked below matrimony. Jerome vigorously takes the other side, and maintains against Helvidius three propositions:

- That Joseph was only putatively, not really, the husband of Mary.

- That the "brethren" of the Lord were his cousins, not his own brethren.

- That virginity is better than the married state.

St. Augustine (4th Century) – “Let us grant that God can do something that we confess we cannot fathom. In such matters the whole explanation of the deed is in the power of the Doer.”

7.3 Assumption and Queen of Heaven

From New Advent:

"In heaven", St. Ambrose tells us, "she leads the choirs of virgin souls; with her the consecrated virgins will one day be numbered."

St. Jerome (Ep. xxxix, Migne, P. L., XXII, 472) already foreshadows that conception of Mary as mother of the human race which was to animate so powerfully the devotion of a later age.

St. Augustine in a famous passage (De nat. et gratis, 36) proclaims Mary's unique privilege of sinlessness.

In St. Gregory Nazianzen's sermon on the martyr St. Cyprian (P.G., XXXV, 1181) we have an account of the maiden Justina, who invoked the Blessed Virgin to preserve her virginity.

But in this, as in some other devotional aspects of early Christian beliefs, the most glowing language seems to be found in the East, and particularly in the Syrian writings of St. Ephraem. It is true that we cannot entirely trust the authenticity of many of the poems attributed to him; the tone, however, of some of the most unquestioned of Ephraem's compositions is still very remarkable.

- Thus in the hymns on the Nativity (6) we read: "Blessed be Mary, who without vows and without prayer in her virginity conceived and brought forth the Lord of all the sons of her companions, who have been or shall be chaste or righteous, priests and kings. Who else lulled a son in her bosom as Mary did? Who ever dared to call her son, Son of the Maker, Son of the Creator, Son of the Most High?"

- Similarly in Hymns 11 and 12 of the same series, Ephraem represents Mary as soliloquizing thus: "The babe that I carry carries me, and He hath lowered His wings and taken and placed me between His pinions and mounted into the air, and a promise has been given me that height and depth shall be my Son's" etc.

This last passage seems to suggest a belief, like that of St. Epiphanius already referred to, that the holy remains of the Virgin Mother were in some miraculous way translated from earth. The fully-developed apocryphal narrative of the "Falling asleep of Mary" probably belongs to a slightly later period, but it seems in this way to be anticipated in the writings of Eastern Fathers of recognized authority.

In any case, the evidence of the Syriac manuscripts proved beyond all question that in the East before the end of the sixth century, and probably very much earlier, devotion to the Blessed Virgin had assumed all those developments which are usually associated with the later Middle Ages.

8 History of Lent

Derivation: The Teutonic word Lent, which we employ to denote the forty days' fast preceding Easter, originally meant no more than the spring season. Still it has been used from the Anglo-Saxon period to translate the more significant Latin term quadragesima (Fr. carême, It. quaresima, Span. cuaresma), meaning the "forty days", or more literally the "fortieth day".

8.1 History

The season of Lent does not appear to have an Apostolic origin, though as early as the Fifth century authors such as St. Leo exhorts his readers to abstain that they may “fulfill with their fasts the Apostolic institution of the forty days”

In the early Church (first three centuries), every Sunday was considered by many to be a celebration of Easter, and Friday before a day of fasting coinciding with the Lord’s death on Calvary. Note: even today, Sundays are considered in this way.) However, there was a yearly celebration of Easter as well. Eusebius wrote, quoting a letter from St. Irenaeus, “for some think they ought to fast for one day, others for two days, and others even for several, while others reckon forty hours both of day and night to their fast”. The forty hours recalls the time that Christ spent in the grave.

8.1.1 The Date of Easter

There was an issue to settle in the early Church as to when the yearly celebration of Easter should take place. This issue was settled in three phases. The first was the day of the week. As stated in the New Advent on line Catholic Encyclopedia:

The dioceses of all Asia, as from an older tradition, held that the fourteenth day of the moon, on which day the Jews were commanded to sacrifice the lamb, should always be observed as the feast of the life-giving pasch [epi tes tou soteriou Pascha heortes], contending that the fast ought to end on that day, whatever day of the week it might happen to be. However it was not the custom of the churches in the rest of the world to end it at this point, as they observed the practice, which from Apostolic tradition has prevailed to the present time, of terminating the fast on no other day than on that of the Resurrection of our Savior. Synods and assemblies of bishops were held on this account, and all with one consent through mutual correspondence drew up an ecclesiastical decree that the mystery of the Resurrection of the Lord should be celebrated on no other day but the Sunday and that we should observe the close of the paschal fast on that day only." These words of the Father of Church History, followed by some extracts which he makes from the controversial letters of the time, tell us almost all that we know concerning the paschal controversy in its first stage.

The second phase was the precise Sunday to celebrate Easter upon. The council of Nicea (c. 325 AD) settled this as stated below, again from New Advent:

- that Easter must be celebrated by all throughout the world on the same Sunday;

- that this Sunday must follow the fourteenth day of the paschal moon;

- that that moon was to be accounted the paschal moon whose fourteenth day followed the spring equinox;

- that some provision should be made, probably by the Church of Alexandria as best skilled in astronomical calculations, for determining the proper date of Easter and communicating it to the rest of the world (see St. Leo to the Emperor Marcian in Migne, P.L., LIV, 1055).

The third phase occurred when Roman missionaries returned Great Britain and Ireland in the time St. Gregory the great and found that the date of Easter there was incorrect. After some bickering, they too were convinced to use the Council of Nicea’s formula.

8.1.2 History of the 40 Days

As indicated above, the fast of Lent was practiced from early in the Church. How did we arrive at 40 days?

Again from New Advent:

In any case it is certain from the "Festal Letters" of St. Athanasius that in 331 the saint enjoined upon his flock a period of forty days of fasting preliminary to, but not inclusive of, the stricter fast of Holy Week, and secondly that in 339 the same Father, after having traveled to Rome and over the greater part of Europe, wrote in the strongest terms to urge this observance upon the people of Alexandria as one that was universally practiced, "to the end that while all the world is fasting, we who are in Egypt should not become a laughing-stock as the only people who do not fast but take our pleasure in those days".

And again:

In Rome, in the fifth century, Lent lasted six weeks, but according to the historian Socrates there were only three weeks of actual fasting, exclusive even then of the Saturday and Sunday and if Duchesne's view may be trusted, these weeks were not continuous, but were the first, the fourth, and sixth of the series, being connected with the ordinations (Christian Worship, 243). Possibly, however, these three weeks had to do with the "scrutinies" preparatory to Baptism, for by some authorities (e.g., A.J. Maclean in his "Recent Discoveries") the duty of fasting along with the candidate for baptism is put forward as the chief influence at work in the development of the forty days. But throughout the Orient generally, with some few exceptions, the same arrangement prevailed as St. Athanasius's "Festal Letters" show us to have obtained in Alexandria, namely, the six weeks of Lent were only preparatory to a fast of exceptional severity maintained during Holy Week.

In the early middle ages throughout most of the Western Church, the duration of Lent had settled into 40 weekdays and six Sundays before Easter. The number 40 of course recalls Jesus’ 40 day fast before the start of his ministry and the 40 years in the desert of the Jews

8.1.3 The Fast

As noted above, the fast was more severe in Holy Week (the last week before Easter). What the fast consisted of changed from place to place and as time progressed. The early Holy Week fast was often a dry fast – that is nothing solid or liquid was consumed for much of the fast. Variety in the nature of the fast is evident. Some abstained from all living creature (animals). Some fasted until none (3PM) and then ate what they wanted. Some abstained from flesh, eggs and milk products. Some ate only dry bread. Some fasted for 24 hours twice a week. The ordinary rule seems to be to have a single meal a day and that only in the evening. St. Gregory, writing to St. Augustine of England laid down the rule, "We abstain from flesh meat, and from all things that come from flesh, as milk, cheese, and eggs." This decision was afterwards enshrined in the "Corpus Juris", and must be regarded as the common law of the Church (New Advent). There seems always to have been room for some dispensations from these fast for those performing heavy labor (they may drink water before the end of the fast, later other drinks such as tea). The general prohibition on eggs and milk may have resulted in the Easter egg custom and the custom of eating pancakes in England. The meal time settled for the most part on midday. Later the practice of parvitas materiae, a small quantity of nourishment was adopted by St Thomas. This quantity was about 8 ounces and taken in the evening. Still later some toast and tea were acceptable in the morning. (This all sounds a lot like our fast requirements of a single meal and two small snacks!) Later still, meat was allowed at some meals during the week, first starting with Sundays, then later various other days of the week (except Friday). After Vatican I, particularly in the US, it was permitted for working men and their families to have meat once per day except on Ash Wednesday, Holy Saturday, Christmas and all Fridays. This was the custom until Vatican II.

8.1.4 Current Regulations

The current Lenten fast regulations are to abstain from meat on Fridays of Lent and Ash Wednesday and to fast on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday. This fast consists of a single meal and two small snacks.

9 Crusades to the Holy Land

The main purpose of the Crusades was to win back access to revered sites in the Holy Land, such as Calvary, Christ’s tomb (Holy Sepulchre), Bethlehem etc. The right to access these sites had been blocked by the Moslem invaders. Islam had conquered Jerusalem in 638. This section highlights some of these Crusades. Though there was the rise of nationalism in this time (fragmentation of the Holy Roman Empire), the Pope was still looked upon with deference and thus nations worked together in the cause of Christendom.

· In 1009, Hakem, the Fatimite Caliph of Egypt orders destruction of Holy Sepulchre and all the Christian establishments in Jerusalem.

· Pilgrimages continued but the rise of the Seljukian Turks compromised the safety of pilgrims and even threatened the independence of the Byzantine Empire and of all Christendom. In 1070 Jerusalem is taken.

· In 1095-1101, Pope Urban II urges the formation of the first Crusade. In 1099 Jerusalem is captured. Christian states are established along Mediterranean.

· In 1145-1147 Louis VII leads Second Crusade to defend Christian states

· Third Crusade from 1188-1192. Richard the Lionhearted and Philip Augustus fight Saladin (who united the Moslems in counter attack)

· Fourth Crusade in 1204. Constantinople taken (and the Orthodox Church and city plundered). This was apparently against the wishes of Pope Inocent III who wished only to recover the Jerusalem in crusade. This did more to hurt relations between East and West than the Filioque problem.

· Fifth Crusade in 1217 conquers Damietta. Crusaders were routed by Saracens in Egypt

· Sixth Cursade in 1228-1229, in which Frederick II took part; also Thibaud De Champagne and Richard of Cornwall (1239). Frederick negotiates treaty of Jaffa and becomes King of Jerusalem

· Seventh Crusade in 1249-1252, led by St Louis (Louis IX, of France) conquers Damietta, is captured and gives it back

· Eighth Crusade, also under St. Louis, 1270. Plague ends this crusade, including the king.

There were many more crusades, but as Europe became more interested in nationalism and leaders more interested in disagreeing with the Church, these became less and less successful.

Bibliography:

1. New Advent Website (http://www.newadvent.org)

2. The Founding of Christendom Vol. 1 by Warren Carroll

3. Catholicism Today, A Survey of Catholic Belief and Practice, Third Edition by Matthew F. Kohmescher

4. Triumph, The Power and the Glory of the Catholic Church by H. W. Crocker III

5. St. Joseph Edition of the New American Bible

6. The Teachings of the Church Fathers edited by John R Willis, S.J., Ignatius Press, San Francisco, 2002